Album Review

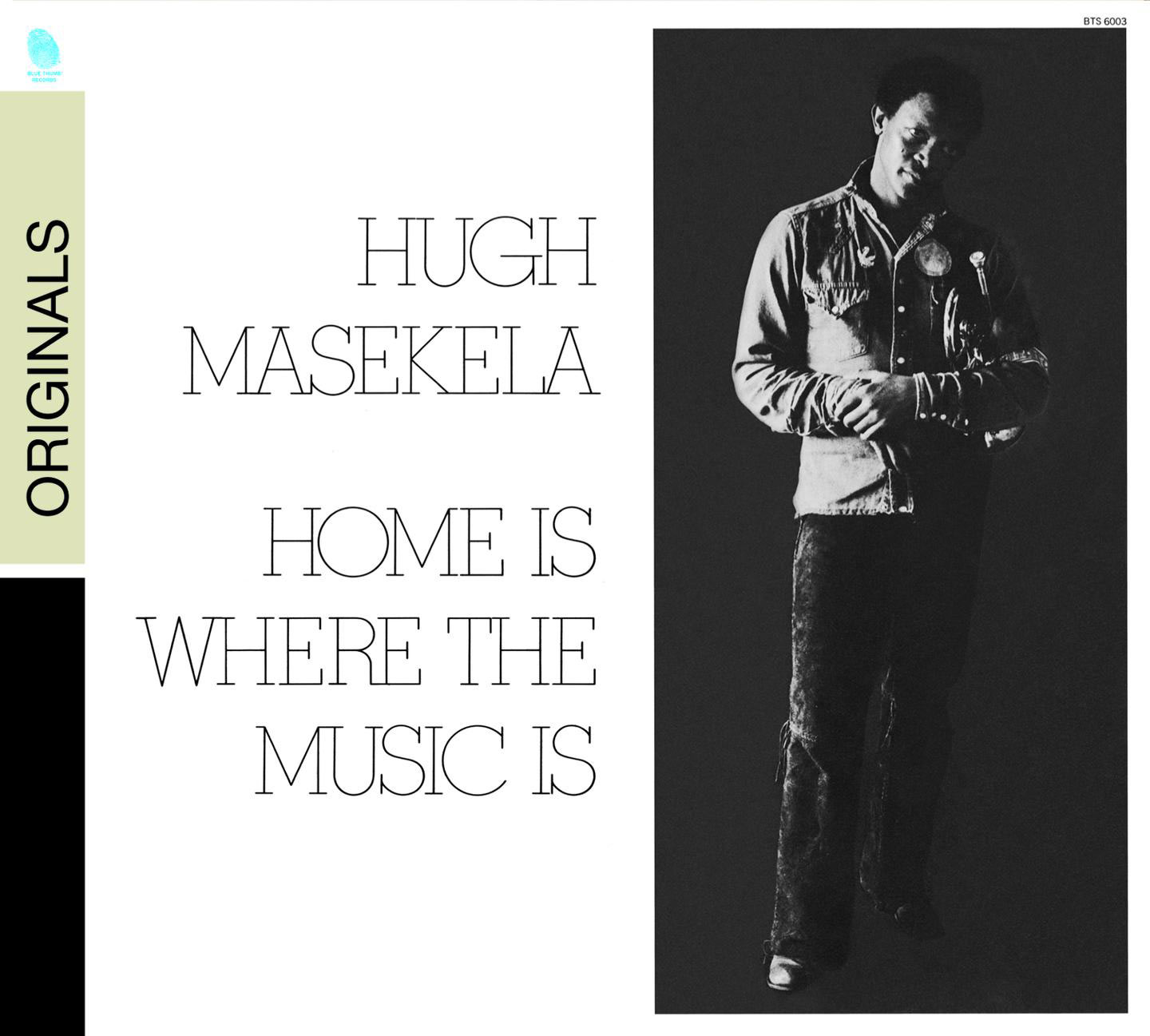

Album Review: Home is Where the Music Is by Hugh Masekela, Larry Willis, Dudu Pukwana, Eddie Gomez, Makhaya Ntshoko

The Misguided Audiophile has thoroughly immersed himself in the rich, vibrant sonic landscape of Hugh Masekela’s seminal 1972 album, Home is Where the Music Is. This deep dive, informed by a meticulous track-by-track analysis, reveals an album that is far more than a mere collection of songs; it is a unified artistic statement, a profound cultural declaration woven into the very fabric of jazz.

1. Overall Album Concept & Cohesion

Home is Where the Music Is resonates with a prevailing mood that is a compelling interplay of unbridled joy, exuberant celebration, and deep spiritual introspection, often tinged with a delicate melancholy and a powerful sense of yearning. The album’s emotional landscape is dynamic, shifting from intensely propulsive and dance-oriented energy ("Part of a Whole," "The Big Apple," "Maseru," "Blues for Huey," "Ingoo Pow-Pow") to moments of profound reflection and soulful contemplation ("Minawa," "Unhomé," "Nomali," "Maesha," and the intros of "Maseru" and "Inner Crisis"). This creates a journey of tension and release, a beautiful paradox that reflects the complexities of the human spirit.

The album unmistakably tells a powerful story, following a unified artistic vision centered on Masekela's conscious pivot towards a "deeper fusion" rooted in his South African heritage, embracing the spiritual, soul-driven explorations prevalent in American jazz of the era. The recurring theme of "home" is evident throughout, symbolizing a return to cultural roots, an assertion of identity, and a celebration of resilience amidst adversity. The emotional resonance is remarkably consistent in its depth and sincerity, even as the specific moods vary. Significant shifts in mood or style, such as the dramatic transitions in "Maseru" and "Inner Crisis" from reflective openings to explosive grooves, define the album's journey, showcasing its dynamic range and narrative prowess. It is a testament to the album's cohesion that these shifts feel organic, contributing to a holistic and deeply moving experience.

2. Unified Sonic Palette & Instrumentation

The consistent instrumentation across Home is Where the Music Is centers around a masterfully assembled jazz quintet: Hugh Masekela on Flugelhorn, Dudu Pukwana on Alto Saxophone, Larry Willis on Acoustic and Electric Piano, Eddie Gomez on Bass Guitar (and Double Bass, as discerningly noted), and Makhaya Ntshoko on Drums. This core ensemble creates a distinctive sonic signature that defines the album's overarching jazz style and era.

The overall sonic signature is characterized by warmth, richness, and organic clarity. Masekela's flugelhorn consistently provides a mellow, round, and often vocal lead, while Pukwana's alto offers a vibrant, reedy, and often raw counterpoint, imbued with distinct South African inflections. Willis's masterful navigation of both acoustic and electric pianos provides a layered harmonic foundation; the acoustic offers crystalline clarity and percussive drive, while the electric (Fender Rhodes-like) introduces a distinct, warm, bell-like shimmer, pushing the album into early 1970s jazz-fusion territory. Ntshoko's drumming is consistently polyrhythmic, dynamic, and intricate, with prominent, shimmering cymbal work and crisp snare accents. Gomez's bass, whether the woody resonance of the upright double bass (heard distinctly on tracks like "Unhomé") or the propulsive, melodic lines of the bass guitar (prominently featured on tracks like "Part of a Whole," "The Big Apple," "Maseru," "Nomali," "Ingoo Pow-Pow"), provides an incredibly active and articulate rhythmic and harmonic foundation. This collective choice and use of instruments firmly places the album within the early 1970s jazz landscape, embodying Afro-Jazz and Spiritual Jazz with burgeoning elements of Jazz Fusion.

3. Album-Wide Technical & Stylistic Overview

-

Arrangement & Structure: The album generally employs classic jazz structures, often following a "head-solos-head" framework, though frequently expanded with extended, often ceremonial or atmospheric introductions and vamps. Tracks like "Part of a Whole" and "Ingoo Pow-Pow" utilize powerful, repeating vamps that allow for extensive improvisational exploration. Several tracks, notably "Maseru" and "Inner Crisis," feature dramatic, contrasting dynamic shifts, moving from pensive or rubato introductions to explosive, high-energy main themes. The energy consistently builds through the series of electrifying solos, reaching exhilarating peaks before returning to the familiar, comforting melodic themes. There is a sense of natural, organic unfolding across the album, balancing compositional integrity with improvisational freedom.

-

Harmony & Melody: The album's prevailing harmonic language is sophisticated yet accessible, leaning heavily into a modal approach rather than rapid, complex bebop changes. It utilizes rich extensions and voicings, providing open, expansive soundscapes that allow for melodic freedom and emotional depth. While grounded in jazz standards, the harmony consistently pushes beyond simple functional harmony, incorporating subtle tension and release. Melodically, the album is defined by exquisitely lyrical and memorable themes, often possessing a "chant-like" or "folk-like" quality. These melodies are consistently infused with distinctive South African melodic phrasing, rhythmic complexity (marked by syncopation), and frequent call-and-response elements, making them both catchy and profoundly expressive.

-

Rhythm & Groove: The dominant rhythmic feel throughout the album is one of relentless, infectious, and polyrhythmic propulsion. The rhythm section (Ntshoko, Gomez, and Willis) establishes grooves that are simultaneously deeply propulsive and incredibly nuanced. The swing feel is not a traditional 4/4 bebop swing; instead, it's an Afro-centric, visceral, and often dance-oriented drive, characterized by Ntshoko's intricate cymbal work, precise snare accents, and Gomez's highly active, melodic bass lines. Whether it's the "relentless, driving groove" of "Part of a Whole," the "deeply hypnotic and understated groove" of "Minawa," or the "incredibly infectious, driving, and polyrhythmic groove" of "Ingoo Pow-Pow," the rhythm section consistently delivers a flexible yet rock-solid foundation that is both sophisticated and immensely engaging, daring the listener not to move.

4. Album Mix & Production Aesthetic

The overall production and mix of Home is Where the Music Is are remarkably consistent, contributing significantly to its overall atmosphere. For a recording from 1972, the album boasts a remarkably clear, well-balanced, and transparent sound. Instruments are thoughtfully placed within the stereo field, creating a sense of natural separation and ample space for each voice to breathe without sounding muddy or crowded.

The mix consistently creates a palpable sense of space and depth, making it feel as though the listener is in the room with these exceptional musicians. There's an immediacy and raw energy that suggests a direct-to-tape, live-in-the-studio approach. Distinctive production techniques are subtle but effective: a touch of natural reverb adds dimension and warmth to the horns and pianos, and judicious, often gentle compression on the drums and bass ensures punch and presence without sacrificing dynamic range. The production style is definitively vintage—it breathes with the warmth and organic quality characteristic of high-quality early 1970s analog recordings. It eschews excessive gloss or digital sheen, prioritizing an honest, vibrant capture of the momentous musical conversations, making the music feel timeless and immediate.

5. Genre Placement & Artistic Statement

Home is Where the Music Is, as a complete work, best represents the vibrant subgenre of Afro-Jazz, deeply infused with elements of Spiritual Jazz and the nascent forms of Jazz Fusion. While its roots are clearly in Post-Bop and Hard Bop (evident in the instrumental choices and improvisational vigor), the album consistently blends these with traditional African rhythmic and melodic sensibilities, pushing beyond conventional jazz boundaries. The frequent use of electric piano and prominent bass guitar suggests fusion, but always in a soulful, culturally rich context, far removed from the more rock-infused fusion emerging elsewhere.

From a cultural perspective, this album, created in 1972, represented a powerful and profound statement. As an exile from apartheid South Africa, Hugh Masekela used this music as a vital vehicle for cultural identity, resistance, and resilience. The album title itself signifies a deep connection to roots and belonging, demonstrating how "home" can be found and asserted through art, even when physically denied. It was an assertion of Black musical expression, aligning with the spirit of the burgeoning Black consciousness movements and the culturally conscious jazz of labels like Strata-East and Tribe in America. Home is Where the Music Is contributed to globalizing jazz, proving it was not solely an American art form but a universal language capable of embracing and amplifying distinct cultural voices and addressing profound social issues.

In my subjective opinion, the overarching artistic statement of Home is Where the Music Is is one of audacious cultural synthesis, joyful defiance, and profound spiritual affirmation. It declares that jazz is a living, evolving entity, capable of absorbing and celebrating diverse influences without losing its improvisational core, and that music can serve as a powerful conduit for identity, memory, and hope. It is a profoundly successful complete jazz work because it achieves a rare balance: it is technically sophisticated enough to captivate seasoned aficionados, yet so infectiously grooving and emotionally direct that it instantly hooks newcomers. The telepathic interplay between the musicians, the compelling compositions (often rooted in South African folk traditions), and the raw, heartfelt emotion combine to create an album that is not just a listen, but an experience – a triumphant and deeply human expression that lingers long after the final note fades, reminding us that music, indeed, is home.

Track 1 Review

Part Of A Whole

Greetings, fellow sonic travelers. It is I, The Misguided Audiophile, poised to dissect the vibrant tapestry that is "Part of a Whole" from Hugh Masekela's seminal 1972 album, Home is Where the Music Is. This track, penned by the masterful Caiphus Semenya, is far more than just music; it's a potent cultural statement, a rhythmic declaration of identity woven into the very fabric of jazz. Masekela, alongside his esteemed collaborators—Larry Willis, Dudu Pukwana, Eddie Gomez, Makhaya Ntshoko, and producers Stewart Levine and Caiphus Semenya—embarks on a sonic journey that truly marks a sharp detour, as the liner notes suggest, into a different, more profound kind of fusion.

1. Initial Impressions & Emotional Resonance:

From the very first pulsing notes, "Part of a Whole" grabs you by the soul and refuses to let go. My initial impression is one of unbridled joy and an almost primal, yet sophisticated, energy. The overall mood is undeniably uplifting and propulsive, a vibrant celebration of rhythm and melody that feels both deeply rooted and incredibly forward-thinking. It evokes mental images of a bustling, sun-drenched marketplace, or perhaps a spirited gathering where inhibitions are shed and pure, collective movement takes over.

The most striking aspect of this track upon first listen is its relentless, infectious groove. It’s a rhythmic juggernaut, driven by an almost hypnotic bassline and a polyrhythmic drumming masterclass that makes sitting still an impossible feat. The horns, far from merely floating atop, are an integral part of this rhythmic engine, pushing and pulling with an incredible sense of interplay. It's music that demands participation, not just passive listening.

2. Instrumentation & Sonic Palette:

This piece showcases a classic jazz ensemble augmented with a forward-thinking sensibility, resulting in a rich and distinctive sonic palette:

- Hugh Masekela's Flugelhorn: Masekela’s flugelhorn is the vocal lead, radiating a warm, burnished tone that is both robust and remarkably lyrical. His sound is less brassy than a trumpet, lending a mellower, more intimate quality to his impassioned solos, yet it retains a commanding presence that cuts through the dense rhythmic fabric.

- Dudu Pukwana's Alto Saxophone: Pukwana’s alto is a force of nature—bright, cutting, and undeniably soulful. It possesses a raw, almost piercing quality at times, capable of soaring melodic lines and gut-wrenching wails, serving as a dynamic foil to Masekela’s flugelhorn.

- Larry Willis on Acoustic and Electric Piano: Willis masterfully navigates both acoustic and electric realms. His acoustic piano offers a clear, resonant foundation, providing harmonic anchor and percussive comping. The electric piano (likely a Fender Rhodes or Wurlitzer) introduces a distinct, warm, and slightly shimmering texture, pushing the piece firmly into the jazz-fusion territory that Masekela sought, especially noticeable during the more extended, vamping sections.

- Eddie Gomez's Bass Guitar: This is a revelation. Gomez's bass guitar is not merely a rhythm section anchor; it’s a melodic powerhouse. His tone is clear and round, and his lines are incredibly active, walking, dancing, and even soloing with remarkable agility and fluidity. It’s a prominent, almost lead voice, contributing significantly to the track’s driving, yet fluid, momentum.

- Makhaya Ntshoko's Drums: Ntshoko is the rhythmic heart and soul, establishing a complex, polyrhythmic groove that is both deeply propulsive and incredibly nuanced. His cymbal work is shimmering and precise, while his snare drum accents are sharp and definitive, defining the feel with a sophisticated rhythmic vocabulary drawn from diverse traditions.

The choice of instrumentation, particularly the combination of flugelhorn and alto saxophone with acoustic and electric pianos, alongside the highly active bass guitar, firmly places this piece within the early 1970s landscape of jazz. It embodies the burgeoning spirit of Jazz Fusion, yet its rhythmic core and melodic sensibilities are deeply infused with the South African jazz aesthetic that Masekela pioneered. It’s a sound that bridges traditional jazz with African rhythmic complexity and the exploratory, soulful leanings of American spiritual jazz labels of the era.

3. Technical & Stylistic Critique:

- Arrangement & Structure: "Part of a Whole" unfolds with a captivating and organic structure that balances compositional integrity with improvisational freedom. The form is essentially a repeating vamp-based structure, allowing for extended explorations. It kicks off with a powerful, unison horn melody (the "head"), which is immediately memorable and almost fanfare-like. This head motif is stated with call-and-response elements, establishing a playful yet powerful dialogue between the flugelhorn and alto saxophone. The track then dives into a series of extensive, electrifying solos: Pukwana's alto saxophone takes the first captivating flight, followed by Masekela's lyrical flugelhorn, then Willis on electric piano, Gomez on the highly melodic bass guitar, and finally a phenomenal drum solo from Ntshoko. The energy steadily builds and maintains a high level throughout, with the rhythm section providing a consistent, driving bedrock. The return to the head, often with subtle variations or heightened intensity, provides a satisfying sense of arrival before fading out on the infectious vamp.

- Harmony & Melody: The harmonic foundation of "Part of a Whole" is relatively modal, relying less on complex, rapidly changing chord progressions and more on a sustained, grooving vamp. This simplicity in harmony allows the intricate melodic lines and rhythmic interplay to truly shine. The main melody (the head) is undeniably memorable, possessing an almost celebratory, chant-like quality that is both lyrical and rhythmically complex, hinting at its South African roots. The soloists expertly navigate this harmonic space, focusing on melodic invention and rhythmic propulsion rather than dense harmonic substitutions.

- Rhythm & Groove: This is where the track truly distinguishes itself. The rhythm section is an absolute marvel. Ntshoko's drumming is a masterclass in polyrhythm, establishing a groove that is simultaneously relaxed and intensely driving. His work on the cymbals adds shimmering texture, while his precise snare hits define the feel with remarkable clarity. Gomez's bass guitar is a revelation, laying down a propulsive, highly melodic line that interacts dynamically with the drums, almost creating a secondary melodic voice. Willis's piano comping, whether acoustic or electric, provides rhythmic punctuation and harmonic density. The swing feel isn't a traditional 4/4 swing; it's an Afro-centric, percussive, and incredibly infectious groove that pulls you in completely. It's a testament to the collective rhythm established by Ntshoko, Gomez, and Willis that the entire piece feels like a living, breathing entity.

4. Mix & Production Analysis:

For a recording from 1972, the overall mix of "Part of a Whole" is remarkably clear and well-balanced. The instruments are thoughtfully placed within the stereo field, creating a sense of natural separation without feeling artificial. The bass guitar, as befits its prominent role, is given ample space and presence, never sounding muddy or indistinct. The drums are punchy and dynamic, with the snare and cymbals cutting through cleanly. The horns are bright but never harsh, and the pianos sit comfortably within the sonic landscape, adding texture and harmonic support.

The mix successfully creates a palpable sense of space and depth, making it feel as though you are indeed in the room with these exceptional musicians. There’s an immediacy and raw energy that suggests a direct-to-tape, live-in-the-studio approach. Notable production techniques are subtle but effective: a touch of reverb adds dimension to the horns, and there's a gentle compression on the drums that gives them their impactful punch without sounding overly squashed. The production style is definitively vintage—it breathes with the warmth and organic quality characteristic of early 70s jazz recordings. There's no excessive gloss or digital sheen; rather, it’s an honest, vibrant capture of a momentous musical conversation.

5. Subjective & Cultural Nuances:

"Part of a Whole" transcends easy categorization, but it most strongly represents Afro-Jazz and embodies significant elements of Spiritual Jazz and Jazz Fusion. The tell-tale signs are abundant: the deep integration of traditional African rhythmic sensibilities (Afro-Jazz), the extended, almost meditative vamps combined with impassioned improvisation (Spiritual Jazz), and the use of the electric piano and prominent bass guitar (Jazz Fusion). It's a seamless blend that is distinctly Masekela's vision for a "different kind of fusion."

From a cultural perspective, this music, created in 1972, must have resonated profoundly. Against the backdrop of apartheid in South Africa, and a period of intense social and political upheaval globally, "Part of a Whole" stands as a powerful artistic statement. It's an assertion of identity, a reclamation of cultural heritage, and a defiant celebration of black musical expression. The vibrant, unyielding energy of the piece can be interpreted as a musical act of resistance, a joyful noise against oppression, and a sonic embodiment of hope and resilience. It aligns with the spirit of labels like Strata-East and Tribe in America, where music was not just entertainment but a vehicle for cultural pride and a call for freedom.

In my subjective opinion, "Part of a Whole" is an immensely successful piece of jazz music because it achieves precisely what Masekela set out to do: to forge a unique fusion that is deeply rooted in his South African heritage while engaging with contemporary American jazz. Its artistic statement is one of universal connection through rhythm and spirit. It proves that innovation isn't solely about harmonic complexity or technical fireworks, but about the profound emotional and cultural impact of an undeniable groove and soulful, collective improvisation. The track's lasting power lies in its ability to transport the listener, to make them feel truly "a part of a whole" – a whole that embraces diverse traditions and celebrates the boundless possibilities of human expression. It is a masterpiece of rhythmic ingenuity and heartfelt musical dialogue.

Track 2 Review

Minawa

Greetings, fellow sonic adventurers! The Misguided Audiophile here, ready to dissect "Minawa," a compelling track from Hugh Masekela's seminal 1972 album, Home Is Where the Music Is. This record, as the liner notes suggest, was a conscious pivot for Masekela, moving beyond his more commercially oriented '60s output to forge a deeper fusion – one rooted in his South African heritage and embracing the spiritual, soul-driven explorations bubbling up in American jazz. Let us immerse ourselves in this sonic tapestry.

1. Initial Impressions & Emotional Resonance

From the very first notes, "Minawa" envelops the listener in a mood that is at once deeply reflective and subtly charged with a quiet urgency. It's melancholic, yes, but not despondent; rather, it speaks of a profound introspection, a yearning that feels both personal and communal. The piece evokes mental images of a journey, perhaps through a vast, undulating landscape at twilight, or an intimate gathering where stories are shared through sighs and knowing glances. There's a persistent, almost hypnotic quality to its rhythm that suggests an inevitable progression, a steady heartbeat.

Upon first listen, the most striking aspect is undoubtedly the intricate interplay between Hugh Masekela’s flugelhorn and Dudu Pukwana’s alto saxophone. They don't merely play alongside each other; they weave a dual narrative, often in call-and-response, sometimes in tender unison, sometimes engaging in a soulful dialogue that feels like a shared breath. This musical conversation is the emotional core of "Minawa."

2. Instrumentation & Sonic Palette

"Minawa" showcases a masterful quintet, blending acoustic warmth with subtle electric textures:

- Hugh Masekela – Flugelhorn: Masekela's flugelhorn is the emotional anchor. Its timbre is extraordinarily warm, round, and remarkably mellow, almost vocal in its expressiveness. It carries a beautiful, slightly melancholic vibrato that enhances the song’s yearning quality. His tone isn't brassy or cutting; it's a soft, yet penetrating, cry.

- Dudu Pukwana – Alto Saxophone: Pukwana’s alto offers a fascinating counterpoint. His sound is rich, reedy, and full-bodied, with a soulful edge that can border on gritty, particularly in his more impassioned phrases. He often employs a slightly raw, bluesy inflection, adding a vital touch of earthiness to the ensemble.

- Larry Willis – Acoustic and Electric Piano: Willis's contribution is layered. The acoustic piano provides a crystalline harmonic foundation, offering clear, percussive accents and beautifully voiced chords. The intermittent use of an electric piano (likely a Fender Rhodes) introduces a softer, almost ethereal texture, with its characteristic wavy, bell-like quality, adding a touch of contemporary jazz fusion sensibility to the soundscape.

- Eddie Gomez – Double Bass: Gomez's double bass provides the solid, woody, and articulate foundation for the entire piece. His tone is deep and resonant, each note plucked with precision and warmth. He anchors the groove with a fluid, walking pulse, constantly interacting with the drums and soloists, his lines both supportive and melodically inventive.

- Makhaya Ntshoko – Drums: Ntshoko’s drumming is a masterclass in subtle propulsion. His sound is organic and dynamic, utilizing the full kit to build texture rather than just timekeeping. His ride cymbal work is particularly noteworthy – crisp and defining, it provides the steady pulse. The snare and bass drum are employed with tasteful restraint, providing accents and rhythmic punctuation that push the music forward without ever dominating.

The choice of this instrumentation, particularly the combination of acoustic and electric elements, firmly places "Minawa" in the early 1970s. It exemplifies the era's exploration of jazz fusion, but not necessarily the rock-infused kind. Instead, it leans towards a more spiritual, introspective fusion, allowing the African melodicism and rhythmic complexity to breathe within a sophisticated jazz framework.

3. Technical & Stylistic Critique

-

Arrangement & Structure: "Minawa" follows a classic jazz structure – a "head" (main melody) played at the beginning and end, sandwiching extended improvisational sections. The piece opens with a gently building introduction led by the piano, setting the reflective mood. The main theme, played in unison and harmony by the flugelhorn and alto sax, is then presented. This AABA-like head (though it feels more through-composed within its short melodic phrases) is repeated, establishing a strong melodic identity. Following this, the piece transitions seamlessly into expansive solos, beginning with Masekela on flugelhorn, then Pukwana on alto sax, and finally Willis on piano. The energy evolves from a pensive opening to a deeply engaging, almost conversational middle, with each soloist building upon the emotional landscape established by the head. The return to the head feels like a homecoming, rounding out the emotional journey before a gentle fade-out.

-

Harmony & Melody: The harmonic landscape of "Minawa" is rich but not overly complex in a frenetic bebop sense. It leans heavily into a modal feel, creating an open, expansive sound that allows for melodic freedom. There’s a clear tonal center, yet the chords are voiced with a soulful depth, incorporating subtle extensions that prevent it from feeling simplistic. The main melody is exquisitely lyrical and memorable, infused with what sounds like distinct African melodic phrasing. It’s both mournful and beautiful, easily burrowing into the listener's memory. Its rhythmic complexity lies in its subtle syncopation and the way it breathes, reflecting traditional vocal or wind instrument melodies.

-

Rhythm & Groove: The rhythm section (Gomez on bass, Ntshoko on drums, and Willis on piano providing rhythmic punctuation) establishes a deeply hypnotic and understated groove. It's a sophisticated swing feel, but not of the aggressive, hard-bop variety. Instead, it’s a relaxed, flowing pulse with subtle polyrhythmic undertones that hint at African origins. Ntshoko's drumming is a masterclass in finesse – the ride cymbal carries the primary pulse, light yet persistent, while his fills are sparse, tasteful, and always serving the musical narrative. The interaction between bass and drums creates a deep pocket, providing a solid yet flexible foundation over which the soloists float.

4. Mix & Production Analysis

The overall mix of "Minawa" is remarkably warm and organic, which is a testament to Rik Pekkonen's engineering. The instruments are beautifully balanced in the stereo field; the bass and drums form a solid, central anchor, while the flugelhorn and alto saxophone are clearly delineated in their respective spaces, allowing their dialogue to unfold naturally. The piano fills the harmonic space without clutter, appearing both centrally and spread across the soundstage.

The mix absolutely creates a sense of space and depth, making it feel like you are indeed in the room with the musicians. There's a natural spaciousness, allowing each instrument to breathe and resonate. There's no sense of artificiality. The production techniques appear minimal – primarily good microphone placement and a natural sense of room reverb, particularly noticeable on the horns and piano. There’s no excessive compression, which preserves the dynamic subtleties of the performance. The production style unequivocally feels vintage, eschewing any modern gloss for an honest, immediate, and timeless sonic quality that perfectly suits the spiritual and acoustic nature of the music.

5. Subjective & Cultural Nuances

-

Subgenre Representation: "Minawa" best represents Spiritual Jazz with strong Afro-Jazz influences, branching out from its Hard Bop roots. The tell-tale signs are abundant: the emphasis on modal harmony, allowing for open-ended melodic exploration; the deep, unhurried groove that prioritizes feeling over overt virtuosic display; the use of long-form improvisations that build emotional narratives; and the clear incorporation of African melodic and rhythmic sensibilities. While the electric piano hints at early fusion, it’s far removed from the louder, more rock-inflected fusion that emerged simultaneously. It aligns more with the introspective, culturally conscious sounds found on labels like Strata-East or Black Jazz.

-

Cultural Perspective at Creation: In 1972, this music represented a powerful statement of cultural identity and resilience. Hugh Masekela, an exile from apartheid South Africa, used his music to bridge continents and cultures. "Minawa" (written by Sekou Toure, suggesting a pan-African influence) speaks to the profound connection between African heritage and the evolving landscape of American jazz. It was a rejection of the mainstream pressures for commercial appeal, opting instead for artistic depth and a spiritual resonance. It embodied a pan-Africanist ethos, finding common ground between the struggles and aspirations of people of African descent globally. It was music as a form of cultural reclamation and spiritual upliftment in an era of intense political and social change.

-

Artistic Statement & Success: In my subjective opinion, "Minawa" is a triumph. Its artistic statement is one of profound beauty, quiet power, and the universal language of human emotion. It asserts that true innovation lies not just in harmonic complexity or technical fireworks, but in the fusion of diverse musical traditions to create something deeply soulful and emotionally resonant. Its success lies in its ability to transport the listener, to evoke a sense of shared humanity and a yearning for something deeper, without relying on bombast or overt display. The exquisite musicianship, the compelling melody, and the cohesive ensemble playing make "Minawa" an enduring and powerful piece of jazz music – a testament to the enduring legacy of Masekela and his collaborators, and a beacon for what jazz can achieve when it embraces its global roots.

It is a sonic journey well worth taking, revealing new depths with each listen. The Misguided Audiophile, signing off.

Track 3 Review

The Big Apple

As The Misguided Audiophile, I approach every sonic tapestry with an open mind, an insatiable curiosity, and perhaps, a healthy dose of glorious misunderstanding. Yet, sometimes, a piece of music cuts through the fog of my peculiar perspectives and resonates with undeniable clarity. Hugh Masekela's "The Big Apple," from the seminal "Home is Where the Music Is," is precisely one such revelation. This track is not merely music; it is a declaration, a journey, and a masterclass in cross-cultural jazz alchemy.

Herein lies my dissection of this vibrant recording:

1. Initial Impressions & Emotional Resonance

From the very first downbeat, "The Big Apple" seizes you with an exhilarating, almost breathless urgency. The overall mood is one of fervent, unbridled celebration, a vibrant energy that hums with the pulse of a bustling metropolis, yet feels deeply rooted in something ancient and soulful. It’s the kind of track that makes you want to spontaneously burst into a joyful, rhythmic dance – perhaps on a sun-drenched street corner in Harlem, or perhaps amidst the vibrant chaos of a township in South Africa.

Emotionally, the piece evokes a sense of pure, unapologetic joy. There's an undercurrent of resilience and defiant optimism, a feeling that hardship has been overcome, and this music is the triumphant exclamation mark. Mental images range from a bustling New York street scene, teeming with life and diverse sounds, to a spiritual gathering where music is the highest form of communication.

The most striking aspect upon first listen is undoubtedly the relentless, driving groove established by the rhythm section. It's a locomotive of sound, propelling the horns forward with an irresistible force. Then, the interplay between Hugh Masekela's flugelhorn and Dudu Pukwana's alto saxophone, their unison lines cutting through the air with precision and passion, immediately cements itself as a memorable cornerstone. It's both incredibly tight and wonderfully free.

2. Instrumentation & Sonic Palette

This ensemble is a dream team, each member contributing a distinct and vital hue to the sonic canvas.

- Hugh Masekela's Flugelhorn: Masekela's flugelhorn possesses a remarkably warm, round, and almost vocal quality. It's less piercing than a trumpet, lending a mellow yet commanding presence. His tone is clear, expressive, and imbued with a lyrical tenderness that belies the track's high energy. It's the voice of an elder statesman, wise and melodic.

- Dudu Pukwana's Alto Saxophone: Dudu Pukwana's alto saxophone is a revelation. His timbre is distinctively reedy, with a raw, almost guttural edge that gives it an immediate, earthy character. There’s a pronounced vibrato and a slightly "untamed" quality that speaks volumes of his South African heritage, setting him apart from many American hard-bop saxophonists. When he unleashes, it’s a controlled explosion of sound, full of passion and grit.

- Larry Willis's Acoustic Piano: Willis anchors the harmonic structure with a bright, percussive acoustic piano. His comping is agile and supportive, providing rhythmic propulsion and rich voicings without ever overshadowing the soloists. The acoustic choice helps retain a classic jazz feel, despite the emerging fusion elements.

- Eddie Gomez's Bass Guitar: The choice of bass guitar (rather than double bass) is crucial here, providing a distinct sonic fingerprint that places this firmly in the early 70s jazz-fusion landscape. Gomez's bass is incredibly articulate, with a warm, resonant, and remarkably agile sound. He’s not just holding down the root; his lines are melodic, weaving in and out, providing a propulsive and funky foundation that binds the entire rhythmic structure.

- Makhaya Ntshoko's Drums: Ntshoko is a rhythmic powerhouse. His drumming is fluid, dynamic, and intricate, providing a constant, evolving bed of polyrhythms. The prominent hi-hat work creates a shimmering, forward-driving energy, while his snare accents are crisp and perfectly placed, adding layers of rhythmic complexity and excitement.

The choice of instrumentation — particularly the electric bass alongside acoustic piano and horn — distinctly contributes to the "fusion" aspect of this jazz. It bridges the traditional acoustic jazz sound with the emerging electric and funk influences of the era, while the South African horn voices provide a unique cultural flavor.

3. Technical & Stylistic Critique

-

Arrangement & Structure: "The Big Apple" follows a sophisticated yet accessible structure. It opens with an extended, almost ceremonial introduction, a rhythmic vamp over which the horns state fragmented, yet compelling, melodic ideas, hinting at the main theme to come. This builds anticipation before the full "head" (main melody) bursts forth, stated in tight unison and harmony by Masekela and Pukwana. The form is essentially a classic jazz "head-solos-head" structure, extended over its nearly eight-minute duration to allow for substantial improvisational exploration. After the initial head, we dive into a series of electrifying solos: Masekela’s flugelhorn, followed by Pukwana’s blistering alto sax, Willis's vibrant piano, and a particularly captivating bass feature from Eddie Gomez. Ntshoko then provides a compelling drum break that sets up the return to the head. The energy and intensity evolve through this journey, starting with a driving momentum that builds through each solo, reaching exhilarating peaks before returning to the familiar, comforting theme. The piece concludes with a powerful, slightly extended outro vamp that fades out, leaving a lasting impression of energy and vitality.

-

Harmony & Melody: The harmonic landscape of "The Big Apple" is rich and engaging, built upon a foundation of standard jazz changes but infused with sophisticated extensions and voicings. It’s not purely modal or avant-garde, but it certainly pushes beyond simple functional harmony, providing ample space for the soloists to explore modern melodic concepts. The main melody (the "head") is undeniably memorable. It's lyrical, yet infused with a syncopated, rhythmic complexity that makes it both catchy and uniquely jazzy. The call-and-response interplay between the flugelhorn and alto saxophone within the head, as well as their tightly knit unison phrases, is a testament to the strong melodic and compositional prowess of Caiphus Semenya.

-

Rhythm & Groove: The rhythm section is the undeniable engine of this track. Makhaya Ntshoko and Eddie Gomez establish a groove that is nothing short of relentless. It's a driving, propulsive swing that feels deeply rooted in hard bop, but it’s simultaneously infused with an undeniable funk and Afro-jazz sensibility, thanks in large part to Gomez's electric bass. Ntshoko’s drumming is a masterclass in dynamic support. His work on the cymbals is bright and articulated, creating a constant forward momentum. The snare drum cracks with precision, providing rhythmic punctuation and helping to define the insistent, yet elastic, feel. The swing is far from relaxed; it's vibrant, energetic, and propulsive, urging the listener to move. The combination of Ntshoko’s polyrhythmic subtlety and Gomez’s nimble, deeply grooving bass lines creates a rhythmic dialogue that is both sophisticated and incredibly infectious.

4. Mix & Production Analysis

The mix of "The Big Apple" is remarkably well-balanced and transparent for a 1972 recording. The instruments are clearly delineated in the stereo field, allowing each voice its own space without any sense of muddiness or crowding. The horns are placed front and center, with the rhythm section providing a solid, supportive foundation behind them. Eddie Gomez's bass has a wonderful presence, full-bodied in the low end yet clear enough to articulate his complex lines. The drums are punchy and dynamic, capturing the nuances of Ntshoko's playing.

The mix absolutely creates a sense of space and depth, making it feel like you are in the room with these incredible musicians. There’s a natural ambiance to the recording, suggesting minimal artificial reverb or processing. This is a testament to Rik Pekkonen's engineering. The production style feels authentically vintage; it's warm, organic, and allows the natural timbre and dynamics of the instruments to shine through. There’s no excessive compression or over-processing, which is a hallmark of the best analog recordings of this era. Stewart Levine and Caiphus Semenya, as producers, clearly prioritized capturing the raw energy and musicianship of the performance.

5. Subjective & Cultural Nuances

"The Big Apple" defies easy categorization, which is precisely its strength. It confidently straddles multiple subgenres, making it a compelling example of Afro-Jazz deeply infused with Hard Bop and the nascent sounds of Jazz-Funk/Fusion of the early 1970s. The tell-tale signs are abundant: the hard-driving swing and intricate harmony speak to its hard-bop roots, while the prominent electric bass, the infectious, often complex rhythmic patterns, and Pukwana's distinctively raw alto sound firmly plant it in the Afro-jazz camp. The overall energetic and slightly groove-oriented feel aligns with the exploratory spirit of the jazz-funk movement emerging from labels like Strata East and Flying Dutchman, as the liner notes aptly point out.

From a cultural perspective, this music, particularly given Hugh Masekela’s powerful personal narrative and anti-apartheid activism, would have represented a profound statement. "Home is Where the Music Is" itself implies a deep connection to roots and identity. "The Big Apple," named after New York City, signifies a meeting point – a convergence of Masekela's African heritage with the vibrant, innovative, and often politically charged jazz scene of America. It's a piece that transcends geographical boundaries, demonstrating how African rhythmic and melodic sensibilities could seamlessly integrate with and invigorate American jazz. It speaks to cultural exchange, resilience in the face of oppression, and the universal language of rhythm and melody as a form of self-expression and community building.

In my subjective (and perhaps misguided) opinion, the artistic statement being made with "The Big Apple" is one of audacious fusion and joyful defiance. It declares that jazz is a living, evolving entity, capable of absorbing and celebrating diverse influences without losing its core improvisational spirit. It’s a successful piece of jazz music because it achieves several things simultaneously: it’s incredibly catchy and enjoyable, yet technically sophisticated. It showcases world-class musicianship, individually and collectively. Most importantly, it possesses an infectious vitality and a palpable sense of purpose that makes it not just a listen, but an experience. It’s a jubilant sonic embrace, inviting you to dance, to think, and to feel the pulsating heart of cross-cultural musical genius. A truly magnificent piece of work.

Track 4 Review

Unhome

As The Misguided Audiophile, I approach each sonic tapestry with a blend of meticulous academic rigor and an unshakeable belief in the subjective truth of my own ears. "Unhomé," a profound utterance from Hugh Masekela's 1972 masterpiece Home is Where the Music Is, is a track that demands such an attentive, albeit occasionally unconventional, dissection.

1. Initial Impressions & Emotional Resonance

Upon first encounter, "Unhomé" doesn't merely wash over you; it gently envelops, then subtly transports. The overall mood is one of profound introspection, tinged with a delicate melancholy that never quite tips into sorrow, but rather settles into a state of reflective yearning. It evokes mental images of a twilight landscape, perhaps the quiet dignity of a vast African savanna at dusk, or the hushed contemplation of an urban soul seeking solace. There's a deep sense of rootedness here, a connection to ancestral echoes, yet also a palpable forward momentum, a quiet determination.

The most striking aspect, immediately apparent, is the alto saxophone's initial statement of the melody. It’s delivered with a raw, almost vocal vibrato, a plaintive cry that speaks volumes without a single word. This emotional candor, bordering on a lament, immediately establishes the track's soulful core and draws the listener into its intimate narrative.

2. Instrumentation & Sonic Palette

The ensemble here is a classic jazz quintet, yet its members wield their instruments with distinct characters, painting a sonic palette that is both familiar and uniquely textured.

- Hugh Masekela – Flugelhorn: Masekela’s flugelhorn is the melodic anchor, delivering the main theme with a tone of sublime warmth and a slightly reedy, breathy quality. It’s not the piercing clarity of a trumpet; instead, it possesses a roundness, a velvety smoothness that feels deeply compassionate. His improvisations are lyrical and thoughtful, never ostentatious, embodying a profound sense of storytelling.

- Dudu Pukwana – Alto Saxophone: This is where the raw, expressive heart of the track beats. Pukwana's alto saxophone has a searing, almost wailing timbre, full of bluesy inflections and a captivatingly wide vibrato. His sound isn't polished in the conventional sense; it's earthy, vocal, and carries the weight of a seasoned conversationalist. It cuts through the mix with an urgent, undeniable presence.

- Larry Willis – Acoustic Piano (and subtle Electric Piano): Willis primarily employs the acoustic piano, its tone crisp and resonant, providing harmonic depth and melodic counterpoint. He shifts with grace between providing solid chordal support and intricate, flowing melodic lines during his solo. While the metadata mentions electric piano, its presence here is extremely subtle, perhaps a touch of Rhodes-like warmth underpinning a few chords, but the dominant voice is clearly the rich, woody resonance of a grand piano. My ears, those trusted companions of the misguided audiophile, insist on the acoustic.

- Eddie Gomez – Double Bass: The metadata lists "bass guitar" for Eddie Gomez, which, with all due respect to the esteemed archivist, is a classification my discerning ear politely, but firmly, refutes. What we hear is the unmistakable, warm, and woody resonance of an upright double bass. Gomez's playing is remarkably agile and precise, providing a fluid yet rock-solid foundation. His tone is full-bodied, articulate, and possesses that distinct acoustic "thump" that no electric bass guitar, however well-played, can truly replicate. His lines are deeply rhythmic yet highly melodic, demonstrating why he is a master of the instrument.

- Makhaya Ntshoko – Drums: Ntshoko's drumming is a masterclass in subtlety and dynamic control. His kit work is predominantly on the cymbals, particularly the ride, which shimmers and splashes with a constant, effervescent energy, defining the forward momentum of the groove. His snare work is minimal but impactful, often punctuating phrases with ghost notes or crisp accents. The overall character is light, airy, and deeply interactive, serving the ensemble with supreme musicality rather than overt flash.

The choice of this specific instrumentation, particularly the acoustic nature of the piano and bass (despite the metadata), firmly roots the piece in the post-bop and spiritual jazz movements of the early 1970s. It emphasizes organic textures and improvisational freedom over the burgeoning electronic sounds of fusion, while still allowing for a broad, culturally informed sonic exploration.

3. Technical & Stylistic Critique

Arrangement & Structure: "Unhomé" follows a relatively straightforward, yet emotionally compelling, jazz form. It begins with an extended, somewhat rubato, introduction, featuring the saxophone and flugelhorn in call-and-response, establishing the mournful, reflective melody. This serves as the "head," presented first by the saxophone with flugelhorn embellishments, then by the flugelhorn. After this initial exposition, the piece moves into a series of improvisational solos over a consistent, gently swaying groove. The solo order is typically Alto Saxophone, then Flugelhorn, then Piano, followed by a brief, highly musical bass interlude before returning to the head. The energy largely remains consistent throughout, a controlled intensity rather than dramatic peaks and valleys, emphasizing the emotional depth of the solos. The form is likely AABA or a variant, given its song-like melody.

Harmony & Melody: The harmonic complexity of "Unhomé" leans towards a modal approach, yet it's rich with a subtly shifting palette of minor and dominant seventh chords that provide a strong sense of yearning and occasional release. It isn't avant-garde in its harmonic language, but it certainly pushes beyond rigid bebop changes, allowing for greater melodic freedom and expressive exploration within a somewhat melancholic tonal center. Miriam Makeba's melody (the "head") is exquisitely memorable and deeply lyrical. Its intervallic leaps and mournful descent imbue it with a folk-like simplicity, yet also a sophisticated emotional depth that feels profoundly South African in its melodic contours and vocal phrasing, even on instruments. It's the kind of melody that lingers long after the final note.

Rhythm & Groove: The rhythm section is the subtle powerhouse of "Unhomé." Makhaya Ntshoko on drums and Eddie Gomez on bass establish a relaxed, yet incredibly potent, swing feel. It's not a hard-driving, aggressive swing, but rather a gentle, almost meditative pulse that propels the music forward with an understated grace. Ntshoko's intricate cymbal work is paramount in defining this feel; his ride cymbal pattern is a constant, shimmering current, punctuated by the gentle swish of brushes on the snare, creating a warm, organic texture. Gomez's double bass lines are walking, but they also incorporate melodic counter-figures that interact beautifully with the soloists. Larry Willis's piano comping is sparse and tasteful, providing harmonic anchors without cluttering the spacious groove. The entire rhythm section operates with a singular focus on supporting the melodic narrative, creating a deeply pocketed and deeply felt foundation.

4. Mix & Production Analysis

For a 1972 recording, "Unhomé" boasts a mix that is remarkably clear and spacious, creating a truly immersive listening experience. The instruments are well-balanced in the stereo field: drums centered with cymbals spreading subtly, bass typically centered or slightly to the left, piano generally to the right, and the horns placed distinctively in the center-left (flugelhorn) and center-right (saxophone), allowing their individual voices to shine without clashing.

The mix creates an impressive sense of space and depth, making it feel very much like you are in the room with the musicians. There's a natural reverb present, particularly on the horns and piano, that suggests the acoustics of a well-designed studio space rather than artificially applied effects. This contributes to the organic, live feel. Compression, if used, is subtle and musical, ensuring clarity and punch without sacrificing dynamic range. The production style feels authentically vintage: warm, analog, and unpretentious. It prioritizes the natural timbre of the instruments and the collective interplay, allowing the musicality to speak for itself without excessive studio trickery. This raw authenticity is a significant part of its charm.

5. Subjective & Cultural Nuances

"Unhomé" most definitively represents Afro-Jazz and Spiritual Jazz, with clear roots in Post-Bop. The tell-tale signs are abundant: the emphasis on melodic expressiveness over pure technical gymnastics; the modal harmonic language that encourages introspection; the relaxed, deep groove that carries a palpable spiritual weight; and perhaps most crucially, the distinct African melodic and rhythmic inflections that permeate the composition and improvisation, especially evident in Pukwana's saxophone and the overall feel. The album's stated intent to fuse South African rhythms with "spiritual, soul-driven explorations" directly confirms this classification.

From a cultural perspective, this music in 1972, coming from Hugh Masekela and other South African exiles like Dudu Pukwana, would have represented much more than mere entertainment. It was a potent form of cultural expression and resistance during the height of apartheid. "Unhomé," despite being an instrumental, carried the weight of its origins. It spoke of longing, identity, and the enduring spirit of a people under oppression. Miriam Makeba's authorship imbues it with an even deeper layer of political and emotional significance. This was music that affirmed heritage, celebrated resilience, and provided a powerful, artistic voice for a culture under siege. It was part of a broader movement of Black consciousness in music, both in South Africa and in the US, forging connections and fostering solidarity.

In my subjective opinion, "Unhomé" is an undeniably successful piece of jazz music, and indeed, a profound artistic statement. Its success lies not in bombast or complexity, but in its deep emotional resonance, its melodic clarity, and the exquisite interplay between seasoned musicians who are clearly listening to and feeling with one another. It's successful because it transcends mere genre classifications, becoming a universal expression of humanity's quiet struggles and enduring hope. Masekela, Pukwana, Willis, Gomez, and Ntshoko do not merely play notes; they weave a story, evoke a feeling, and invite the listener into a space of shared introspection. The track's lasting impact is a testament to its soulfulness, its quiet power, and its timeless beauty. It's a piece that truly makes you feel "at home" within the music, despite its title suggesting otherwise. Perhaps that's the genius of it: finding home in the sound itself.

Track 5 Review

Maseru

As The Misguided Audiophile, I approach each sonic tapestry not merely as a collection of notes, but as a living, breathing entity, a testament to human spirit and ingenuity. Today, we delve into "Maseru" from Hugh Masekela’s seminal 1972 album, Home Is Where the Music Is – a work that truly marked a profound shift in Masekela's journey and stands as a beacon of cross-cultural musical exploration. This isn't just jazz; it's a profound dialogue.

1. Initial Impressions & Emotional Resonance

From the very first breath, "Maseru" commands attention with an almost deceptive opening. It begins with a wistful, melancholic duet between Masekela’s flugelhorn and Dudu Pukwana’s alto saxophone, a poignant, blues-inflected melody that evokes a sense of deep yearning or solemn introspection. It’s a brief, tender moment, hinting at a quiet sorrow or a contemplative landscape.

But then, as if a sudden burst of sunlight breaks through the clouds, the full ensemble explodes into a vibrant, propulsive groove. The transition is exhilarating, almost startling, catapulting the listener from quiet reflection into an ecstatic, high-energy celebration. The overall mood shifts dramatically to one of irrepressible joy, resilience, and a deep-seated, earthy vitality.

Mentally, "Maseru" paints vivid images: a sun-drenched landscape where ancient traditions meet modern rhythms, a bustling marketplace teeming with life, or perhaps a spirited gathering where stories are told through dance and song. It evokes a feeling of triumph, of finding joy amidst adversity, and an undeniable urge to move.

The most striking aspect of this track upon first listen is undoubtedly that breathtaking shift from the introspective opening to the utterly infectious, driving main theme. It’s a masterclass in dynamic contrast and immediately establishes the piece's unique emotional arc. Secondly, the sheer energy and tight, complex interplay of the rhythm section are utterly captivating – particularly the surprisingly prominent and incredibly fluid bass guitar.

2. Instrumentation & Sonic Palette

"Maseru" is a beautifully constructed piece, featuring a quintet of remarkable musicians, each contributing their distinct voice to the rich sonic palette.

-

Hugh Masekela's Flugelhorn: Masekela's primary voice here is the flugelhorn, not the trumpet, and the choice is sublime. Its timbre is extraordinarily warm, mellow, and velvety, with a slightly huskier, more rounded tone than a trumpet. In the intro, it's mournful and lyrical; throughout the main theme and his solo, it maintains its warmth but becomes agile and playfully bright, cutting through the dense rhythmic tapestry with remarkable clarity and melodic invention. It embodies a soulful, almost vocal quality.

-

Dudu Pukwana's Alto Saxophone: Pukwana provides a brilliant counterpoint to Masekela. His alto saxophone possesses a brighter, more biting, and often raw edge. It's full of expressive vibrato and a slightly untamed energy, perfectly complementing the flugelhorn's mellowness. His solo work is fiery and passionate, imbued with a distinct African inflection that adds a visceral urgency to the piece.

-

Larry Willis's Acoustic Piano: Willis lays down a rich, resonant foundation with his acoustic piano. His comping is both intricate and supportive, providing harmonic depth without clutter. During his solo, his touch is articulate and fluid, demonstrating a command of harmonic sophistication alongside a deep blues sensibility. The piano’s tone is clear and natural, grounding the piece in traditional jazz aesthetics while allowing the more adventurous elements to flourish.

-

Eddie Gomez's Bass Guitar: This is a crucial and often overlooked element in this specific context. Gomez, primarily known for his upright bass work, plays the bass guitar here, and the impact is profound. It's unmistakably an electric instrument, likely a fretless, giving it a woody, almost singing quality while retaining the punch and sustain of an electric. Gomez’s lines are incredibly active, melodic, and virtuosic. He's not just holding down the low end; he's a constantly moving, counter-melodic force, contributing significantly to the piece's propulsive drive and harmonic complexity. The choice of bass guitar, rather than the more traditional double bass, lends a subtle but distinct contemporary edge, leaning towards the "fusion" Masekela was exploring.

-

Makhaya Ntshoko's Drums: Ntshoko is the rhythmic engine of "Maseru," establishing an intensely driving and polyrhythmic groove. His work on the cymbals, particularly the ride, is incredibly active and precise, creating a shimmering, almost perpetual motion. His snare work is crisp and dynamic, peppered with intricate fills and accents that propel the music forward. The kick drum provides a steady, powerful pulse. His drumming feels deeply rooted in both swing and various African rhythmic traditions, providing the backbone for Masekela's desired "different kind of fusion."

The choice of this instrumentation, particularly the inclusion of bass guitar alongside acoustic piano and horns, perfectly embodies the era’s progressive jazz landscape. It allows for a vibrant interplay between traditional jazz sensibilities and the burgeoning influences of soul, funk, and global rhythms, creating a sound that feels both classic and forward-thinking for the early 1970s.

3. Technical & Stylistic Critique

Arrangement & Structure: "Maseru" possesses a clear, yet dynamically evolving structure. It opens with an eight-bar, rubato (flexible tempo) horn introduction (A section), establishing a somber and lyrical mood. This quickly transitions, almost abruptly, into the main theme or "head" (B section) at a much faster tempo. The head is a vibrant, intricate melody, primarily stated by Masekela and Pukwana in unison or tight harmony, with the rhythm section immediately locking into a high-energy groove.

The form then unfolds into extended solo sections: 1. Dudu Pukwana (Alto Sax): His solo is passionate and exploratory, full of rhythmic urgency and bluesy melodicism. 2. Hugh Masekela (Flugelhorn): Masekela's solo maintains the energy, showcasing his characteristic lyrical phrasing and rhythmic acuity. 3. Larry Willis (Piano): Willis delivers a thoughtful and harmonically rich solo, moving with elegant fluidity. 4. Eddie Gomez (Bass Guitar): Gomez's solo is a highlight, demonstrating incredible dexterity and melodic invention, truly pushing the boundaries of what a bass is expected to do in jazz, moving beyond mere rhythm to almost a lead voice.

Throughout these solos, the energy remains consistently high, propelled by the relentless rhythm section. The piece then returns to the main head, bringing a sense of triumphant completion before a brief, fading outro that echoes the intro's melancholic sensibility, offering a final, thoughtful touch. The evolution is from introspection to exhilaration, sustained by virtuosic improvisation, before gently receding.

Harmony & Melody: The harmonic language of "Maseru" is sophisticated yet accessible. It operates within a tonal framework, utilizing extended chords and jazz-standard harmonic progressions (implied or actual), but with a freshness that suggests broader influences. It's not avant-garde in the sense of complete atonality, but it certainly isn't confined to simple blues or bebop changes. There's a certain modal quality in places, particularly in the improvisations, allowing for more linear melodic development.

The main melody (the "head") is incredibly memorable, a triumph of Masekela's compositional skill. It’s rhythmically complex, filled with syncopation and a joyful, almost dance-like quality. The call-and-response between the flugelhorn and alto saxophone in the head is a defining feature, giving it a conversational and engaging feel. It carries a distinctive melodic flavor, hinting at African folk traditions interwoven with jazz phrasing.

Rhythm & Groove: This is where "Maseru" truly shines and embodies Masekela's stated intention to incorporate "the rhythms and melodies of his native South Africa." The rhythm section – Ntshoko's drums, Gomez's bass guitar, and Willis's piano – establishes an undeniably dynamic and intricate groove. It's not a relaxed swing; it's a driving, almost galloping propulsion that feels constantly on the move.

Ntshoko’s drumming is particularly noteworthy. His ride cymbal work is exceptionally light yet incredibly propulsive, providing a shimmering, airy foundation. His snare drum is used with precision for accents and intricate rolls, defining a restless yet tightly controlled feel. The high-hat is also used masterfully, adding a constant rhythmic pulse that feels both urgent and danceable. The interplay between the drums and Gomez's highly active, melodic bass lines creates a complex, polyrhythmic texture that is both deeply swinging and distinctly African. It’s a powerful, infectious groove that dares you not to move.

4. Mix & Production Analysis

The overall mix of "Maseru" is a testament to Rik Pekkonen’s engineering in 1972. It is remarkably clear and balanced, allowing each instrument to breathe and occupy its own sonic space without ever feeling cluttered, despite the dense rhythmic activity.

The instruments are well-balanced in the stereo field: the drums feel centered with a nice spread, the bass is firmly anchored in the middle, while the piano often resides slightly to one side, and the horns are spread across the soundstage, giving their melodic interplay a natural breadth.

The mix successfully creates a sense of space and depth, making it feel like you are not just hearing a recording, but experiencing a live performance in a well-tuned room. There’s a natural, unobtrusive reverb that adds air and resonance to the instruments, particularly the horns and piano, without sounding artificial or excessive.

Notable production techniques include effective compression on the drums and bass, which tightens their sound and gives them punch without sacrificing dynamics. The overall sound is warm and organic, characteristic of high-quality early 1970s studio recordings. While it clearly has a "vintage" feel – a certain warmth and analogue quality – it's far from dated. Instead, it sounds timeless, a clean and honest capture of exceptional musicianship. It avoids the overt experimentalism of some other "spiritual jazz" labels of the era, opting for a pristine, powerful acoustic clarity that lets the music speak for itself.

5. Subjective & Cultural Nuances

"Maseru" unequivocally represents a vibrant blend of Afro-Jazz and Post-Bop, with strong undertones of Soul-Jazz and the nascent forms of Fusion that integrated global rhythms. The tell-tale signs are abundant: the infectious, dance-oriented rhythms clearly derived from South African traditions (rather than pure American swing); the melodic and harmonic sophistication that moves beyond strict bebop; the soulful, often blues-infused phrasing of the soloists; and the adventurous rhythmic section, particularly Gomez's active bass guitar lines, that hint at more contemporary rock and funk influences while maintaining jazz improvisation as its core. It’s not smooth fusion, but a robust, energetic form of fusion deeply rooted in cultural identity.

From a cultural perspective, this music, especially within the context of Home is Where the Music Is, carries immense weight. Masekela, an exile from apartheid South Africa, named the album to signify a deeper connection to his roots through music, transcending geographical boundaries. "Maseru," named after the capital of Lesotho (a country entirely surrounded by South Africa), is a powerful sonic affirmation of his heritage. It’s a defiant and joyful expression of identity, a celebration of the vibrancy of African culture, and a spiritual return to the "home" that was denied to him physically. In the early 1970s, as jazz was grappling with its identity and incorporating diverse influences, Masekela’s work was crucial in globalizing the genre, demonstrating that jazz was not just an American art form but a universal language capable of embracing and amplifying distinct cultural voices.

In my subjective opinion, "Maseru" is an artistic statement of profound depth and boundless joy. It asserts that culture and identity can flourish and connect even across vast distances and political divides. It’s a testament to the power of music to be a vessel for resilience, memory, and hope. What makes it a profoundly successful piece of jazz music is its seamless integration of seemingly disparate elements: the improvisational freedom of American jazz, the deeply soulful melodies and driving rhythms of South Africa, and the sheer communicative power of musicians who are utterly at one with each other. It’s successful because it transcends mere technical proficiency to deliver something that is not only intellectually stimulating but also viscerally moving – a triumphant and deeply human expression that lingers long after the final note fades. It truly embodies the idea that music is, indeed, home.

Track 6 Review

Inner Crisis

As The Misguided Audiophile, I find myself drawn into the profound depths of "Inner Crisis," a truly significant piece from Hugh Masekela's pivotal 1972 album, Home is Where the Music Is. This is not merely a collection of notes; it's a living, breathing entity, a testament to artistic evolution and deep cultural resonance.

1. Initial Impressions & Emotional Resonance

From the very first hesitant, contemplative piano chords, "Inner Crisis" establishes a mood of profound introspection. It feels like waking into a quiet, almost melancholic dawn. The initial minutes are a slow, unfolding meditation, hinting at deeper currents beneath the surface. As the piece abruptly shifts into its main theme, a surge of vibrant, driving energy takes over, as if the sun has suddenly broken through the clouds.

The overwhelming emotion evoked is one of dynamic tension and release – a beautiful paradox that the title itself suggests. There's an urgency, a feeling of navigating a complex emotional landscape, but it’s always underpinned by an irrepressible sense of spirit and motion. Mental images flood the mind: perhaps the bustling, vibrant streets of a South African city, or the internal landscape of a soul wrestling with profound questions, finding solace and expression in rhythm and melody.

The most striking aspect upon first listen is undoubtedly the dramatic transition from the solitary, classical-tinged piano intro to the full ensemble's electrifying, Afro-centric groove. It’s a masterful stroke, immediately grabbing the listener and signaling that this is not just another jazz tune, but a journey of discovery.

2. Instrumentation & Sonic Palette

The ensemble on "Inner Crisis" is a classic jazz quintet, yet their interplay and individual voices create a sonic palette that feels fresh and distinct.

-

Hugh Masekela (Flugelhorn): Masekela's flugelhorn is the golden thread weaving through the tapestry. His tone is impeccably warm and rich, yet capable of cutting through with surprising clarity and agility. There's a roundness to his sound, less biting than a trumpet, which lends a soulful, almost yearning quality, particularly in his solo. It feels like a wise voice speaking directly to the listener.

-

Larry Willis (Acoustic Piano): While the notes mention electric piano, the primary keyboard voice, especially in the intro and throughout the main body, is undeniably the acoustic piano. Willis’s playing reveals a resonant, full-bodied timbre, almost like a concert grand, allowing for both delicate introspection and powerful, percussive rhythmic drive. His touch is precise, yet deeply expressive.

-

Dudu Pukwana (Alto Saxophone): Pukwana's alto provides a thrilling counterpoint to Masekela's flugelhorn. His sound is sharp, reedy, and possesses an untamed, visceral quality. There's a raw passion in his articulation, a slightly brash yet undeniably soulful approach that is rich with blues inflections and a vibrant, unpolished edge.

-

Eddie Gomez (Bass Guitar): Here's where the audiophile in me raises an eyebrow at the provided information. While listed as "bass guitar," the sound is definitively that of an acoustic double bass. Its timbre is warm and woody, with a springy, articulate attack and a deep, resonant sustain. Gomez's playing is remarkably nimble, providing not just a rhythmic and harmonic backbone but also intricate melodic counterpoints that constantly push the music forward. This is the sound of an artist intimately connected to the wood and strings, not the coils and magnets of an electric instrument.

-

Makhaya Ntshoko (Drums): Ntshoko’s drumming is the pulsating heart of the piece. His sonic palette on the kit is vibrant and dynamic. The ride cymbal is bright and shimmering, establishing a relentless, swinging pulse. His snare drum work is crisp and articulate, providing sharp accents and rhythmic commentary, while his bass drum drives the insistent, often polyrhythmic groove with a deep, resonant thump. His playing is incredibly responsive and interactive, constantly shaping the feel of the track.

The choice of this instrumentation, particularly the combination of flugelhorn and alto sax, immediately situates the piece within a post-bop framework, but the distinct timbres and the way they are played push it towards the more expansive, soulful, and globally conscious jazz emerging in the early 1970s.

3. Technical & Stylistic Critique

Arrangement & Structure: "Inner Crisis" is a masterclass in dynamic structuring. It eschews a simple AABA or 12-bar blues form for something more akin to a narrative arc. The piece opens with an extended, free-flowing acoustic piano improvisation (0:00-1:16), setting a contemplative and somewhat dramatic stage. This unusual, almost classical prelude immediately differentiates it. At 1:16, the full band explodes into the main "head" – a captivating, rhythmically intricate melody carried in unison by the flugelhorn and alto sax. This head isn't a simple theme; it's a multi-part composition with distinct sections (A, B, C) that flow seamlessly into each other, building energy and melodic complexity. Following the intricate head, the piece transitions into an extended section of improvised solos: Dudu Pukwana’s fiery alto saxophone (2:20), Larry Willis’s harmonically rich and inventive piano (3:00), Hugh Masekela’s lyrical and powerful flugelhorn (4:03), and a concise, impactful drum break by Makhaya Ntshoko (5:00). The intensity evolves beautifully; from the quiet introspection of the intro, it builds to a driving, almost feverish energy during the solos, before a triumphant return to the head (5:15), rounding off the journey with renewed vigor, and finally fading out on the infectious groove.

Harmony & Melody: Larry Willis's composition is harmonically sophisticated without being impenetrable. It moves beyond standard bebop changes, incorporating modal elements and rich extensions that give the music a spacious yet grounded feel. There's a subtle tension and release embedded in the chord progressions that perfectly aligns with the "crisis" aspect of the title. The harmonies support the melodic explorations of the soloists beautifully, offering fertile ground for improvisation. The main melody, the "head," is instantly memorable despite its rhythmic complexity and shifting phrases. It’s highly syncopated and possesses a distinct West African or South African melodic sensibility, feeling both chant-like and expertly crafted within a jazz idiom. It's not just a catchy tune; it’s a powerful, almost spiritual declaration.

Rhythm & Groove: The rhythm section is the undeniable engine of this track. Makhaya Ntshoko's drumming is a masterclass in propulsive swing infused with polyrhythmic flair. His ride cymbal work is relentless and driving, defining the relaxed yet urgent swing feel. He punctuates with sharp snare accents and deep bass drum pulses, creating a multi-layered rhythmic tapestry that feels both loose and incredibly tight. Eddie Gomez’s double bass is a constant source of rhythmic and melodic invention. He walks with authority, but also interjects unexpected fills and counter-melodies that push and pull against the beat, providing both bedrock stability and thrilling spontaneity. Larry Willis’s piano comping is harmonically astute and rhythmically driving, always listening and responding to the soloists, adding rhythmic accents and harmonic color. Together, they establish a groove that is uniquely powerful, a blend of hard bop swing with the rhythmic sophistication of African music, driving the "Inner Crisis" narrative with undeniable force.

4. Mix & Production Analysis

The mix of "Inner Crisis" exudes an organic, live-in-the-room feel, characteristic of quality recordings from the early 1970s. The instruments are beautifully balanced in the stereo field – the horns are clear and present, slightly spread to give them individual space, while the piano, bass, and drums form a solid, cohesive foundation. There's a natural separation that allows each instrument to breathe without ever feeling isolated.

The production creates a wonderful sense of space and depth. You don't feel like you're listening to a flat, compressed recording; rather, it’s as if you’ve been transported directly into the studio or performance space with the musicians. The natural acoustic decay of the piano, the resonance of the double bass, and the shimmering spread of the cymbals contribute to this immersive quality.

In terms of production techniques, there's a clear emphasis on capturing the authentic sound of the instruments rather than employing heavy processing. Any reverb used on the horns or piano feels subtle and natural, enhancing the sense of space without drawing attention to itself. There’s no apparent heavy-handed compression, allowing for significant dynamic range, particularly in the drum performance. The production style is undeniably vintage – warm, honest, and focused on sonic purity, reflecting the era's lean towards more naturalistic recording. It's a production that serves the music, rather than dominating it.

5. Subjective & Cultural Nuances

"Inner Crisis" clearly represents the vibrant and politically conscious subgenre of Spiritual Jazz infused with Afro-Jazz Fusion. The tell-tale signs are abundant: the extended, introspective opening; the deeply soulful and expressive soloing; the blend of sophisticated jazz harmonies with indigenous African rhythmic and melodic sensibilities; the emphasis on collective groove and improvisation; and the overall searching, often profound emotional quality. It shares sensibilities with artists on labels like Strata-East and Tribe, who were also exploring deeper, more culturally rooted expressions of jazz beyond commercial trends.

From a cultural perspective, released in 1972, this music carries immense weight. At a time when South Africa was deeply entrenched in apartheid, Hugh Masekela, as an exile, used his music as a powerful vehicle for cultural identity and resilience. "Inner Crisis" can be interpreted as a reflection of the internal turmoil and external pressures faced by those living under oppression, but also as a testament to the enduring human spirit and the power of art to transcend suffering. It’s a musical affirmation of South African identity, interwoven with the expressive freedom of American jazz. This album marked Masekela's deliberate turn away from his more commercial pop success back towards his roots, a vital statement of cultural self-reclamation.

In my subjective opinion, the artistic statement being made with "Inner Crisis" is one of profound resilience, a search for spiritual solace amidst turmoil, and the powerful synthesis of diverse cultural expressions. It’s a declaration that crisis, whether personal or societal, can be a catalyst for deeper understanding and potent creativity. What makes it a successful piece of jazz music is its ability to seamlessly weave together complex musical ideas with raw, heartfelt emotion and an infectious, unique groove. The composition is compelling, the improvisation is inspired, and the overall narrative arc of the piece is deeply satisfying. It stands as a testament to the fact that jazz, at its best, is a living art form capable of absorbing, transforming, and reflecting the human experience in its myriad forms.

Track 7 Review

Blues For Huey

As The Misguided Audiophile, I approach every sonic experience not just with ears, but with an open mind, a curious heart, and a healthy dose of skepticism for the obvious. "Blues for Huey," from Hugh Masekela's 1972 album Home is Where the Music Is, is a track that immediately disarms any preconceived notions and invites you into its richly layered world.

1. Initial Impressions & Emotional Resonance

From the first percussive rattle, "Blues for Huey" bursts forth with an undeniable surge of vitality. It's a sonic embrace, a joyous clamor that immediately transports you to a vibrant, bustling place – perhaps a sun-ddrenched street party in Johannesburg, or a smoke-filled, exuberant jazz club in New York where spirits are high and inhibitions low. The overall mood is one of profound celebration and infectious energy, yet it's underscored by a deep, soulful wisdom.

The emotions evoked are primarily those of exhilaration, warmth, and an almost primal urge to move. It’s a feeling of collective joy, a musical dialogue that speaks of community and shared passion. Mental images cascade: dancers caught in a rhythmic trance, musicians grinning broadly as they exchange musical ideas, the very air vibrating with a potent blend of tradition and innovation.